21st century is a century of digitization. The penetration of digital technology has seen an increasing pace over the last two decades; however, Covid-19 pandemic has suddenly broadened the envelope due to pressing demands and dependency on digital tech. In this light, Digital Public Goods (DPGs) assume the centre-stage and should form the core of any ongoing and future policy interventions to realise the goals of governance and make it agile, resilient and future ready. When reflecting on the last decade, the change has been staggering – much of it because of the advent of digital technologies which are now at a tipping point.

In their simplest of forms, DPGs are open-source software. Content and data, ranging from early-grade reading applications for children to complex systems that governments can use to allocate unique digital identities to populations. DPGs can cut costs for lower-income countries by improving access to state-of-the-art and adaptable core technologies.

DPGs can help us be better prepared for future eventualities. Just as importantly, they have the potential to transform the prospects of countries throughout the world, and usher in a new era of international cooperation.

The Pandemic Push

While the pandemic spelt doom for a lot of things which existed in the pre-pandemic world, green shoots are visible courtesy technology and digital solutions. The pandemic has made two things evident: Digitalisation will fuel the developing world out of economic hardships and digitalisation of the medium, small and micro (MSME) sector is a necessary ingredient for it, as MSMEs are major drivers of economy with a large impact footprint, both negative and positive.

The pandemic has given rise to economic reforms in many developing countries; the need for social distancing has pushed for the adoption of digitalisation by governments, companies, consumers, educational institutions and NGOs; the increasing affordability of technology and prediction makes it accessible and possible; and platforms are the new institutions – now easier to build and participate in. At the cusp of this new era, how can we ensure equity and a level playing field in digitalisation? There are some challenges to consider, as this process is still fundamentally different in developed and developing countries.

DPGs for global commons

Digital Public Goods (DPG) are non-excludable and non-rivalrous. The UN defines DPGs as “Open source software, open data, open AI models, open standards and open content that adhere to privacy and other applicable international and domestic laws, standards and best practices, and do no harm, and help attain the SDGs [Sustainable Development Goals].” DPGs are aimed at achieving the SDGs. For instance, District Health Information Software 2 (DHIS2) is a free and open source health management data platform used by multiple organisations, and a total 54 countries. The creation and promotion of digital public goods for the purpose of addressing rising concentration in digital markets, however, is a new phenomenon being witnessed in India.

The Genesis

Two years ago (In 2019), UNICEF and the Government of Norway began incubating a concerted effort to promote digital public goods as a push to advancing the Sustainable Development Goals. The Digital Public Goods Alliance (DPGA) was thus born as a multi-stakeholder initiative to facilitate the discovery, development, use, and investment in digital public goods. The DPGA is now endorsed by the UN Secretary-General's Roadmap for Digital Cooperation. It holds great promise we see for such technologies to help address some of the most urgent global challenges the world is facing.

DPGs: An institutionalization for vision 2030

New technologies are now being used at national scale to deliver better services to citizens. Stakeholders use digital technology as a key lever to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Public provisioning of digital infrastructure – that is, treating these resources as a public good that anyone can use without charge (non-excludable) and without preventing others from using it (non-rivalrous) – will revolutionize progress towards Agenda 2030.

The Dry run:

Countries are now seeing concrete results from embracing this digital technology. In South Africa, mobile messaging that provides essential information to new or expectant mothers has now scaled to cover 95% of the market. In India, Aadhaar, a national system that uses biometric and geographic data to generate a unique ID (an essential aspect for social, economic, and political inclusion), has registered 1.21 billion subscribers and achieved an estimated $13 billion2 in reduced transaction overhead.

Multilaterals donor consortiums are focusing on digital technology too. The World Bank’s ID4D program is working to scale national identification platforms while tackling data privacy issues at the same time. Financial services companies, government regulators and others are using open source software like Mojaloop to take on the challenges of interoperability of financial systems to deepen financial inclusion and are looking to pool their investments in fewer, larger digital platforms.

Estonia’s digital citizen identification system and Xroad federated data exchange infrastructure founded on privacy-by-design principles has enabled the creation of an inclusive public service delivery system in the country where over 2000 services can be accessed online. In India, the Ministry of Commerce’s proposal for re-tooling the Government e Marketplace (GeM) platform for online government procurement into a publicly-owned business to customer marketplace can provide a fillip to micro, small and medium enterprises.

Creating Digital Public Goods

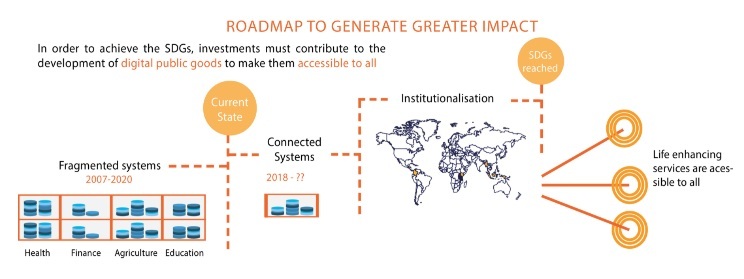

Despite the progress we are seeing, there is still much work to be done to evolve from a world of sectoral digital building blocks to a connected system that leads to the routine use of digital technology. In the end, the goal should be to recognize such a system as a collective set of “digital public goods” to be shared by all for the benefit of everyone.

Digital public goods are appropriate digital platforms and service products, pricing and procurement mechanisms, training programs for people and supportive digital policy that protects private citizens. The Digital Impact Alliance for instance develops open source digital public goods that anyone can take and adapt (open-source). If carefully designed based on the four Ps – products, pricing, policy and people programs – these goods can be adapted to move from fragmented digital investments which do not operate at scale to digital platforms and services that run national government infrastructure with services that can reach anyone.

If the SDGs are to be met by 2030, it will require a global cross-sector commitment to collaborate on investing in digital public goods such as reusable digital platforms and data algorithms; negotiated pricing and pooled procurement mechanisms; increased digital capabilities at the citizen and governmental level and a sincere focus on a responsible regulatory regime that protects citizens’ rights, investments in peoples digital capabilities and stronger policy advocacy are required. Moving on these issues can move digital technology from novelty to an institutional lever to achieve the SDGs.

The Tech Conundrum: Global North-South Divide

First, there’s a difference between ‘access’ and ‘usage’ of technology. The issue facing the developed world is ‘usage’, that is, consumer privacy, security, data protection, productivity. The developing world needs ‘access’ – digital availability, affordability and usage of infrastructure. Second, there’s a ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ infrastructure gap – ‘hard’ includes devices, electricity, telecom, servers, data centres, while ‘soft’ includes digital platforms, content, legal and policy measures across value-chains. The developing world lacks both.

The world is also tied down to three approaches: proprietary digital platforms owned by a few private players, a government mandated system, and a broad regulation for consumers disconnected from their needs. A universalist approach is necessary to reconcile these worlds. One way is by making digitalisation a ‘public good’ – available, affordable, accessible, auditable, scalable, with privacy embedded in its design. The UN secretary general laid this out in his substantive road map for digital cooperation.

Models

India

A ready and demonstrated model of digital public goods is available in India, in the form of IndiaStack – a set of open, modular, interoperable protocols, building blocks that allow “governments, businesses, startups and developers to utilise a unique digital infrastructure to solve India’s hard problems”. It can be compared to the public highways which governments finance and build – on which private and public vehicles can drive, commerce can thrive and people can prosper.

The base of this is a biometric identity, connected to bank accounts through which citizens receive services and subsidies, from pensions to remittances, licences to food rations. The identity stores the digital records – but consent of sharing data lies with the individual. It has been tested during the pandemic across India’s vast, diverse population, and at continental scale – with food rations for migrant workers, vaccines taken and digital certificates provided.

World

The Philippines, Morocco, Ethiopia, are working with MOSIP, or the Modular Open-Source Identity Platform, a not-for-profit foundation offering the open-source code. The UN high-level panel for digital cooperation endorsed MOSIP in its June 2020 report.

Digital goods for post pandemic world: Key to unlock

Once the pandemic ends, the focus will be on getting people back to work, and this is where digital public goods are critical, especially to revive MSMEs. In developing countries, they are plagued by low digitalisation and poor access to low-cost and easily available credit. In the absence of data, the costs of reaching these MSMEs, underwriting, monitoring and repayment risks of small-sized loans, make it difficult for lenders to provide credit.

India Story

India is democratising credit flows to MSMEs while simultaneously driving digitalisation within them – this is Microfinance 4.0. Building blocks such as the Open Credit Enablement Network (OCEN) bring together private participants like app-based companies, credit-scoring, mutual funds, insurance, telcos, which can innovate across the entire lending value chain.

Sustainability??

We cannot forget to consider sustainability. Massive digitalisation requires mountains of silicon chips, magnets and batteries, which need rare earths and lithium, all difficult to mine. Data centres are responsible for 1% of global energy consumption. Chip-making is water-intensive, and the chemicals are polluting. The need of the hour is yes, more digitalisation, but also innovation for a smart, non-polluting chip. Till that comes, the hope is for democratic digitalisation to create new tiger economies, across continents – in the Indo-Pacific, Africa, South America, the Caribbean. It’s more possible now than ever before.

DPGs and Regulation by State

Until now, the state only enters into an otherwise free market ether to check some form of market failure or to ensure equity through regulation. Regulation is typically a legal command to firms to adhere to certain norms of behaviour in a marketplace. For instance, in the telecommunications sector, a firm with Significant Market Power (SMP) cannot price its products/services below cost price. Where regulation is aimed at checking the wrongful exercise of market power, it complements competition law. Regulation may also enjoin positive duties. Universal Service Obligation (essentially a form of cross-subsidy) is one such example through which states ensure that rural and unprofitable areas too access telecommunications services.

The creation and promotion of digital public goods for the purpose of addressing rising concentration in digital markets, however, is a new phenomenon being witnessed in India.

Digital markets, due to their technological and corresponding features, are prone to concentration. The world over, jurisdictions such as the EU, Germany, US and Korea are struggling to create rules that would ensure that digital markets stay competitive. India is a prominent stakeholder in this process with its lucrative digital markets.

Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture (DEPA)

IndiaStack is a set of open and standardised APIs that act as open highways for data transfer. While previous layers of IndiaStack such as Aadhar, eKYC and Digilocker were not necessarily meant to foster competition, Unified Payments Interface (UPI) and the latest DEPA are examples where standardised APIs are aimed to foster competition.

DEPA is a techno-legal architecture—a joint public-private effort— that is aimed at breaking data silos by allowing seamless data transfer between data controllers and data users through an intermediary called Consent Manager (CM). CM acts as a dashboard where a user can track her consent, decide the scope and also withdraw the consent. The data transfer happens through APIs with the consent of the data user. In this architecture, APIs play a crucial role. Standardised and open APIs provide for an interoperable system, where new data users and data providers can ‘plug in’ into the data-sharing ecosystem without any hassle.

In the financial sector, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) took the lead in standardising APIs and made them available to all. In addition, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) set out a consent artefact (a machine-readable electronic document that specifies the parameters and scope of data share that a user consents to in any data sharing transaction).

Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC)

While the immediate motivation behind DEPA is to give users more control over their data, competition is a natural outcome. Fostering competition through digital public goods is more immediately visible in the Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC) initiative. ONDC is a government-supported e-commerce platform. ONDC aims to integrate different e-commerce ecosystems into one solution. This means it will be akin to a ‘platform of platforms’. It is an open e-commerce platform that provides interoperability in the sense that a buyer registered on Amazon may directly purchase goods from a seller who sells on Flipkart. ONDC is planned as an open network developed on open-sourced methodology, using open specifications and open network protocols independent of any specific platform. Once again, this architecture will be based on open APIs.

As soon as a seller features on any nodal e-commerce platform, it automatically features on ONDC. The ONDC architect can check several practices that have kept antitrust agencies busy the world over. Listing on ONDC means sellers are not subjected to the rules/guidelines of nodal platforms—this is the most critical feature. This may avoid, self-preferencing, downgrading in ranking, deplatforming, exclusive dealing etc.

Challenges

1. Public data pools

Public data pools are pivotal to unlock the public value of data and ‘digital intelligence’ (the sociological description of AI) and build an inclusive digital innovation environment. This imperative assumes greater significance in a global digital economy founded on the bed rock of data extractivism. However, such data pools prove to be difficult to create, especially in countries of the Global South where legacy public data sets may not exist in annotated and machine-readable form and born-digital data from their territories is captured by transnational digital companies. Instituting mandatory data sharing obligations on the private sector to share data sets that are deemed to be of critical public importance then becomes essential in this scenario.

2. Data as an economic resource

Balancing the interests of data principals, innovators who build digital intelligence solutions from data, the rights of individuals/communities affected by such intelligence innovations, and the broader public interest, is necessary to ensure that data resources are deployed towards inclusive and sustainable development. A framework to govern access, use and control rights in data has to effectively navigate multiple and conflicting interests. This calls for a well-evolved legal imaginary of data ownership. Existing legal frameworks predominantly account for the rights of database creators/compilers, either through copyright/ contract law (the US standard) or a sui generis right of database owners preventing reutilisation (the EU standard). In the wake of the privacy debate, emerging frameworks to confer individual control tend to reduce ownership over personal data to consent-based self determination, which is an unsatisfactory solution. Individual agency and choice in the platform economy is constrained, with users unable to leave dominant monopoly platforms and having to agree to complex and unintelligible terms of use. Further, the boundaries of personal data mining for economic activity also entails societal and public interest, automatically impinging upon a vast user base, and cannot be a matter of individual preference.

3. Essential platform utilities

In the digital economy, dominant platforms such as Google, Amazon and Facebook have become crucial mediators of economic and social interactions. These platform behemoths control entire economic ecosystems, exercising three distinct forms of power: gatekeeping power to determine their membership; transmission power to direct, determine and manipulate activity flows among their members; and scoring power for indexing/ranking that influences decisions by actors in the ecosystems they control. Dominant platforms assume the character of a quasi-public essential infrastructure.

The roadmap for the future

Digitising and annotating existing public data across sectors, especially, social sectors such as health, and opening up such public data for open public use in a machine readable form is an important step. This can lay the foundation for startups and enterprises to build applications and services. Public support for the development of natural language processing technologies in local languages can create standards across data sets, and allow interoperability at a large scale. Based on the twin principles of collective ownership and individual control, projects like DECODE – Decentralized Citizen Owned Data Ecosystem –, funded by the European Commission, have sought to explore how common benefits from data can be harnessed, while vesting with citizens the ability to give and revoke consent for any or all uses of data. Other ideas proposed by the UNCTAD Digital Economy Report 2019 include, commissioning the private sector to build the necessary infrastructure for extracting data, which can be stored in a public data fund that is part of the national data commons. The city of Barcelona is testing a similar system using public procurement contracts to mandate companies (such as Vodafone) to provide the government with the data they collect which it could use for the benefit of the people.

To enable the effective governance of public data pools in a manner that balances competing and conflicting interests in data, appropriate policy frameworks are needed. They need to recognise different categories of access, use and control rights over individual/personal and social-behavioural/ non-personal data sets, along the continuum from public good to private property. In a mixed data economy ownership regime, state agencies will have the powers to create public data pools by encouraging voluntary data sharing by citizens and instituting mandatory data sharing measures for private corporations. In the creation and governance of such public data pools, only de-identified personal data sets may be integrated in order to prevent privacy violations. Private firms may be asked to relinquish their exclusive rights over data collected and processed as part of their business where such data is assessed to be of national importance. In case of cultural/knowledge commons or community data, the terms of inclusion in public data pools must ensure that collective rights of local communities in such data are not compromised. Conditionalities about the type of intelligence innovations that can be created on top of such data sets will be necessary to prevent expropriation of the public data commons for private gain. Preferential access for digital start-ups and public research activities will be important.

Jurisdictional sovereignty over data resources, including the right to institute data localisation measures as per strategic economic considerations, is a cornerstone principle for governments. Developing countries need to preserve this space in trade policy negotiations.

FRAND (Fair, Reasonable and Non-Discriminatory) licensing and compulsory licensing conditionalities for AI innovation can go a long way in enabling developing countries leapfrog current development trajectories.

Current remedies to curbing the risks of privatisation of essential platform infrastructure focus on a) preventing consumer harm stemming from the abuse of market dominance by powerful platforms and b) introducing tighter rules for mergers and start-up acquisitions through which powerful incumbents could further entrench their market advantage. While these approaches are important, they do not address the core problem of reclaiming the public utility character of foundational digital infrastructure. In this regard, two types of structuralist interventions need to be considered: a) preventing platform companies providing essential platform infrastructure from operating in other parts of the value chain in the digital economy and competing with its clients (such as forcing Amazon to choose between Amazon Web Services and its e-commerce marketplace and divest stakes in one of them; or preventing Facebook from launching digital payments solutions) and b) investment in building public options to dominant platforms.

Democratising technology with the five foundational attributes of universal access, bias towards inclusion, sacrosanct rights, direct recourse to the law and continuous innovation is essential to uphold techno-citizenship and, consequently, techno-sovereignty in this new world order driven by technology and digital platforms. The pandemic has only served to accelerate the world toward this inevitable conclusion. India is a first mover in this novel idea of democratising technology and developing digital public goods. The world must now come together with forward momentum on these five attributes to usher an era of ‘tech for all’ and ‘tech by all.’

Verifying, please be patient.