Introduction

- There is a silent “water war” ongoing in India i.e. the conflict over paradigms of water governance.

- It is a global phenomenon that has persisted over the last four decades ever since Western countries realised that large-scale dam building and structural interventions had been fragmenting river systems and leading to irreversible ecosystem destruction at the basin scale.

- In 2000, the European Union (EU) adopted the Water Framework Directive, following which a series of dam decommissioning happened across Europe.

- Since then, some 5,000 such structural interventions have been decommissioned in France, Sweden, Finland, Spain and the United Kingdom.

- In India, however, this worldwide call for a shift to Integrated Water Resource Management has so far eluded the water technocracy.

- Indian hydro-technocracy has remained adherent to archaic notions of water resource development that considers short-term economic benefits while ignoring long-term sustainability concerns.

- It has also opposed any change from the status quo.

India’s Approach to Water Management

In the past few years, the administration has made certain efforts to steer the country towards integrated water governance.

In 2016 two bills were drafted:

- The Draft National Water Framework Bill 2016 (NWFB), and the Model Bill for the Conservation, Protection, Regulation and Management of Groundwater 2016.

- In the same year, the report, A 21st Century Institutional Architecture for India’s Water Reforms, was released.

The Report recommended that both the Central Water Commission (CWC) and Central Ground Water Board (CGWB) be dissolved, and in their stead be created a multi-disciplinary National Water Commission (NWC). This is indeed a rational recommendation, given that groundwater and surface water are not separate entities but integral components of the same hydrological system, and therefore need to be governed using a holistic basin ecosystem governance approach. The Report called for a multidisciplinary approach to governing waters through the involvement of social scientists, natural scientists, and professionals from management, and other specialised disciplines.

The Global Paradigm Debate

There is enough evidence that the ‘business as usual’ way of managing water has become unsustainable, and would lead to severe stress, and even possibly conflicts between stakeholders. The last few years therefore witnessed the increasingly ubiquitous call for change in the existing visions of managing water. The new thinking entails replacing the reductionist engineering-centred paradigm by a new holistic and interdisciplinary notion.

There is no doubt that the progress of the present civilisation is marked by human ability to build bigger engineering structures that modify the flow regimes through storage and diversion.

- In conjunction with gaining control over the aquifers through stronger pumping technologies, surface water controls were achieved through large dams effectively used for controlling floods and generating hydro-electricity at a massive scale.

- This offered reasonable protection against seasonal water shortages and even spatial inequities in water availability.

- The irrigation canals made it possible for humans to grow food in newer as much as it enhanced the growing seasons for crops.

- Over time, it became a predominant view that water scarcity is spatial, and that water can be diverted to the water-scarce zones from the water-rich ones, through appropriate supply augmentation plans.

- In order for water to be distributed equitably so the thought process explained supply should be expanded through interventions in the natural hydrological flows

Such strategies indeed resulted in impressive successes in providing larger supplies to water-scarce regions. The successes were short-term, though, and over time it became clear that the new and emerging challenges of the future are much more complex than scarcity. Concerns heightened that following a strategy that single-mindedly sought to increase intervention into the hydrological cycle were becoming counter-productive as they led to adverse impacts on basin ecosystems. This brought about the call for a holistic knowledge base, identified as IWRM.

Elements of water governance:

- Democratic elements: In the process including transparency, accountability, and decisive participation of the people on ground.

- Institutional Mechanism

- Constitutional provisions

- Legal Framework

- Planning and decision-making processes

Integrated Water Governance at the basin scale

The recognition that there is an imperative for a holistic approach in managing water and governing river basins is reflected in policymaking in different countries. Apart from dam decommissioning, other means to conserve water in stream are being undertaken in various countries across the world.

- In Australia, for example, the Murray-Darling Basin Commission is contemplating on extending financial assistance to farmers who save on their allocation of irrigation water and allow these savings to remain in stream.

- Meanwhile, in Chile, the National Water Code of 1981 established a system of water rights that are transferable and independent of land use and ownership. The most frequent transaction in Chile’s water markets is the ‘renting’ of water between neighboring farmers with different water requirements.

- More recently, in December 2019 in Chicago, water derivatives trading began at the Mercantile Exchange in order to combat water availability risk in the US west. This is a significant development towards demand management after years of structural interventions that affected river courses in western US.

- The most critical issue here is to acknowledge the need for a systems approach to water governance, in general, and of river basins in particular. River basins are integrated and all parts are linked to changes in others, over space and time.

- Such changes may be part of either natural processes or else are human-induced. Flows in rivers are not only of water with dissolved chemicals, especially in the conditions prevailing in India, they also carry sediments, energy and biodiversity, and tinkering with any of them will impact all the others.

- The activity taking place in one part of the basin (e.g. disposal of waste water, deforestation of watersheds) will have impacts in all downstream parts.

- For example, the construction of the Farakka barrage on the lower Ganges in India commissioned in 1975 is blamed for inhibiting sediment flow further downstream into the delta, thereby restricting soil formation. Successive flood damages in Bihar in 2016 have also been attributed to the sediment accumulation behind the barrage.

What can be done for proper Water Governance?

- Water needs to be viewed as a flow and an integral component of the Eco hydrological cycle, rather than as a stock of material resource to be used according to human requirement and convenience.

- From an economic perspective, water has value in all its competing uses including for those of the ecosystems (to be recognised through valuation of ecosystem services associated with water and flow regimes). Therefore, water should be recognised as an economic good in its broader ecological economic interactivity. From a social perspective, this cannot preclude the affordability and equity criteria.

- The river basin should be the unit of governance.

- Supply of ever increasing volumes of water is not a prerequisite for continued economic growth or even for food security. Rather, options need to be sought in water-saving technologies.

- There is a need for comprehensive assessment of water development projects within the framework of the full hydrological cycle.

- A transparent and interdisciplinary knowledge base for understanding thesocial, ecological and economic roles played by water resources is required.

- Droughts and floods are to be visualised in the wider context of the ecological processes associated with them.

- It is important to devise an integrated approach towards policymaking, decision-making, and cost-sharing across various sectors in the basin including industry, agriculture, urban development, navigation, ecosystems, taking into consideration the poverty reduction strategies.

- It is important to create a solid foundation and repository of multidisciplinary knowledge of the river basin and the natural and socio-economic forces that influence it.

- Gender considerations are important, and as recognised in the Dublin Statement, women play a central part in the provision, management and safeguarding of water.”

Water Dispute in India

- The Interstate River Water Disputes Amendment Bill 2019 seeks to improve the inter-state water disputes resolution by setting up a permanent tribunal supported by a deliberative mechanism the dispute resolution committee.

- The Dam Safety Bill 2019 aims to deal with the risks of India’s ageing dams, with the help of a comprehensive federal institutional framework comprising committees and authorities for dam safety at national and state levels.

- There is less significant body of analyses about state of water governance in India and our unique challenges and opportunities.

The Cauvery Water Conflict

- The conflict over the Cauvery basin in India between the states of Karnataka and Tamil Nadu is also a reflection of the fragmented piecemeal approach of the water governance architecture in India.

- While water being a State subject in the Indian Constitution already leads to a fragmented nature of basin utilisation accentuating the conflict (a phenomenon described as “conflictual federalism”) deeper economic analysis also reveals that the galloping minimum support prices favouring the production of water-consuming irrigated paddy has also led to increased competing demand for water between the two states.

- The Supreme Court judgment of February 2018 brought about some changes in this allocation between the states by acknowledging urban water use through reduction of allocation of the Cauvery Waters for Tamil Nadu from 192 TMC to 177.25 TMC annually. The remainder 14.75 TMC was allocated to Karnataka for the growing city of Bangalore.

- Though in one sense, this judgment calls for better agricultural water management on the part of Tamil Nadu, the fundamental structure of the CWT Award hardly changes as the cause of the ecosystem remains unaddressed.

Challenges:

- Groundwater Governance

- Environment Management Challenges

- Water Pollution

- Equity and Distribution

- Corruption

- Food Production

- Water Supply and Sanitation

Food security definition and irrigation networks

The Indian delineation and action towards food security have been resource-intensive, and was largely based on the reductionist engineering-based approaches of supply-augmentation. The Green Revolution in the late 1960s, introduction of minimum support price (MSP) mechanism in the late 1970s, and governmental procurement policies led to food security being viewed through the lens of production and procurement of two major water-consuming food grains, i.e., rice and wheat. While the Green revolution led to rise in yield levels, the MSPs of the two staples were increased at a much faster rate than the less water-consuming millets in an attempt to promote their production and easy procurement.

MSP acted as a financial derivative instrument for hedging, “put option”: if prices fall below the MSP, there is an option of selling rice/ wheat at the MSP to the state. Over time, MSP became the “floor” price-setter for rice and wheat, as whenever MSPs for rice and wheat were increased by the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP), the traders put across a higher bid, thereby increasing the market prices of the two food grains.

- This moved the terms-of-trade (defined as ratio of prices of two competing crops, e.g. rice and millets) substantially in favour of rice and wheat with acreages moving in favour of water consuming staples and displacing drier millets that require around 10-20 percent of the water needed by paddy.

- This phenomenon prevailed in many parts of India, e.g. in the Krishna and Cauvery basins or in the Upper Ganges in Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh, where irrigated wheat and/or paddy became the dominant crop during the non-monsoon summer months, and were produced as the third crop of the cropping year. This led to substantial increase in groundwater extraction and surface water diversions.

Though agricultural economists argue that this irrigation in India is largely groundwater-dependent, it needs to be kept in mind that groundwater depletion due to overuse is creating pressure on surface flows. At the same time, it is often forgotten that groundwater feeds and sustains the surface flows. Over time, in large parts of southern India, canal irrigation became prevalent, taking a heavy toll on surface flows. Essentially, the “agricultural economic” perspective supported by “reductionist engineering” thinking of water management through constructions of large irrigation projects have accentuated water conflicts all because of a wrong vision of “food security” defined in terms of production and procurement of high-water consuming, and resource-intensive crops. This is in contravention with global scientific literature and best practices that state that water and food security need not have a simple positive-linear relation.

Rather, there are several best-practice-mechanisms of water management that delink the two variables.

- In large parts of south Asia, agricultural expansions have caused widespread changes that degrade the ecosystems and restrict their ability to support critical services including food provisioning.

- The ecological foundation of the food system has been challenged by extensive use of fertilisers and pesticides that impair the natural soil fertility in large parts of south and northern India.

- The natural soil formation function of ecosystem through sediments is also impaired by large constructions that impede the sediment carrying capacity of rivers.

Conclusion

The current water governance paradigm that is reliant on structural interventions over water flows has become unsustainable. The existing dispensation of water technocracy appears to have no intention of instituting reforms in policy, and calls for change have been subjected to attacks from the lobby that continue to believe in the status quo.

Such resistance to change needs to be understood from the perspective of deeply entrenched visions of structural interventions to govern rivers that have historical origins in India’s colonial era.

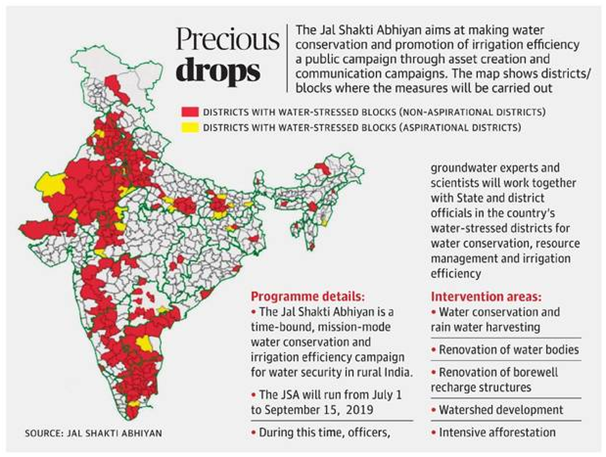

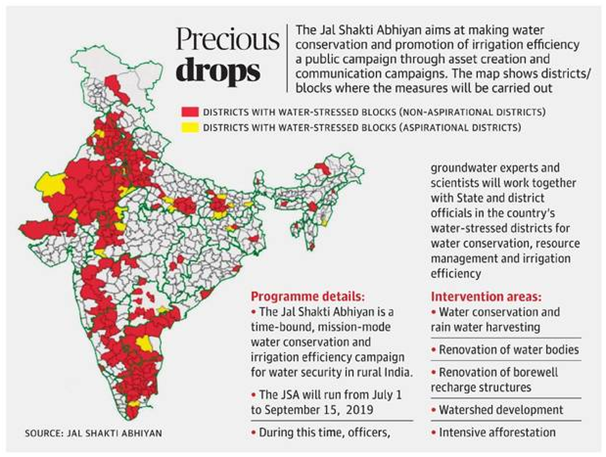

- The idea of the multidisciplinary approach to water governance as suggested in the 2016 Report seems to be resonating well with the Ministry of Jal Shakti.

- In November 2019 the ministry constituted a committee to draft a new National Water Policy (NWP). Violating past trends, the committee consists of a group of multidisciplinary professionals.

The colonial engineering paradigm that embodied the metabolic rift between human and nature has to be replaced by a more interdisciplinary thinking combining engineering with social and ecological sciences.