Context

The agriculture sector’s massive greenhouse gas emissions pose a threat to India’s green transition. There is an urgent need for a transition to climate-smart crops.

Background

- During British Raj, India faced drastic feminine. After independence, the country was determined to become self-sufficient in producing food grains and not to depend on other countries for food sufficiency.

- However, India had been importing wheat from the US under Public Law 480 (PL480) since 1954.

- The situation mutually benefitted India and the US until the India-Pakistan war in the summer of 1965, and the subsequent condemnation of US actions in Vietnam by India, which led to an immediate threat of withdrawal of the PL480 programme by the US.

- By this time, India’s urban labouring class had become dependent on PL480 wheat supplied to them through the ration shop system.

- In order to become self-sufficient, India launched Green Revolution in 1965 under the leadership of the Lal Bahadur Shastri and with the help ofS. Swaminathan.

- S. Swaminathan played a vital role in introducing high-yielding varieties of wheat in India to increase agriculture production in India.

- He is also known as the father of green revolution in India.

- He is an Indian geneticist; under his guidance and supervision, high-yielding varieties of wheat and rice were grown in the fields of Indian states.

- In India, the green revolution continued from 1965 to 1977.

- It mainly increased the food crops production in the state of Punjab, Haryana and Western UPand enabled India to change its status from a food deficient country to one of the leading agricultural nations in the world.

- However, today the sector faces enormous environmental issues, which needs to be addressed at the earliest.

Analysis

Contribution of Agriculture Sector

- The agriculture sector is an integral part of India’s growth story.

- Economic benefit: It employs 58 percent of the population and contributes 18 percent of the country’s GDP.

- In the first quarter of 2020, agriculture was the only sector that showed some growth (3.4 percent) when the economy contracted overall by a massive 23.4 percent.

- Food security: It is responsible for both food and nutritional security and is key to efforts towards alleviating poverty and reducing inequality.

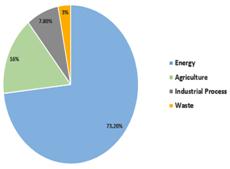

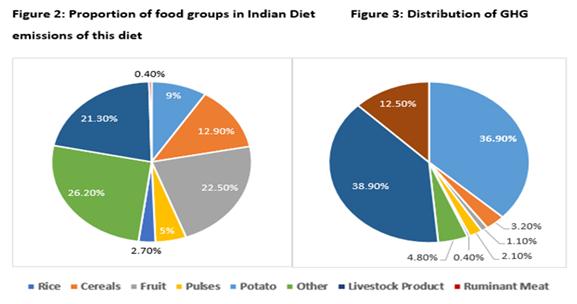

- Contribution to GHG: At the same time, agriculture contributes 16 percent of the total greenhouse gas emissions in the country, second only to the energy sector.

Why agriculture is becoming a ‘concern’?

- Expanding population, increasing burden on land: To feed an expanding population, the annual world food production will need to increase by 60 percent over the next three deca

- Climate Change, adding difficulty level: Climate change will undermine agricultural production systems and food systems, especially in agricultural communities in developing countries where poverty, hunger and malnutrition are the most prevalent.

- Contribution to GHG: The agricultural sector itself, which include crop and livestock production, forestry, fisheries and aquaculture, is also a major contributor to global greenhouse gas emissions.

How does the sector contribute to GHG?

- Most farm-related emissions come in the form of methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O).

- Cattle belching (CH4) and the addition of natural or synthetic fertilizers and wastes to soils (N2O) represent the largest sources, making up 65 percentof agricultural emissions globally.

- Smaller sources include manure management, rice cultivation, field burning of crop residues, and fuel use on farms.

- At the farm level, the relative size of different sources will vary widely depending on the type of products grown, farming practices employed, and natural factors such as weather, topography, and hydrology.

Important International Reports

- In September 2020, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) released a report that says that the food production line of the world accounts for about a quarter (21 to 37 percent) of GHG emitted every year due to human activities.

- The food production line involves everything from growing and harvesting crops to processing, transporting, marketing, consumption and disposal of food and related items

- It sustains around 7.8 billion people.

- This means, food system is as polluting as sectors like electricity and heat production (which accounts for 25 percent of GHGs) and industry (21 percent), and are more polluting than transportation (14 percent) and buildings and energy use (16 percent).

|

How rice (specifically) adds to GHG emissions?

- Rice is the staple food for more than 65 percent of the Indian population and contributes 40 percent of total food grain production in India.

- It occupies a central role in Indian agriculture as it provides food and livelihood security to a large proportion of the rural population.

- In 2018-19, India produced 116.42 million tonnes of rice, second in the world only to China.

- However, rice cultivation is a considerable threat to sustainable agriculture as it is a significant source of GHG emissions (e.g., methane and nitrite oxide).

- Rice is a significant sequester of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

- Furthermore, emission of methane (or CH4)from flooded paddy fields, combined with the burning of rice residues such as husks and straws, further add to GHG emissions.

- In 2017, India produced 112.78 million tonnes of rice, which led to large emissions as summarised in the following table.

Emission Content of Rice Cultivation in India

|

Rice Cultivation

|

Value 2017

|

Unit

|

|

Implied emission factor for CH4

|

10.556

|

g CH4/m2

|

|

Emissions (CH4)

|

4622.3668

|

gigagrams

|

|

Emissions (CO2eq)

|

97069.7036

|

gigagrams

|

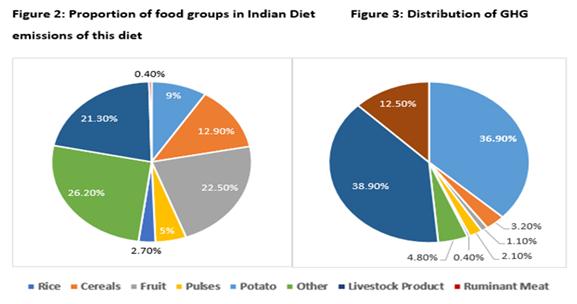

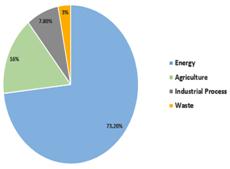

- While rice formed only 9 percent of total consumption in Indian diets, it contributed 9 percent to the total GHG emissions in Indian diets.

Why Indian farmers are fascinated with rice?

- Handsome incentives: Indian farmers are incentivised to produce rice because of an assured demand at a remunerative price.

- Assured demand: The assured demand for rice had been a motivator towards its production. On the other hand, the lack of such demand for millets and pulses has forced a decline in their production over the years. Thus, income support and demand are crucial facilitators for production of any desirable climate-smart crop.

- Subsidised inputs: It is also the availability of subsidised inputs for one set of food grains over the other that further promotes the production of the former.

Is climate-smart agriculture, the future?

- To step up and face the many challenges in agriculture, the solution lies in climate-smart agriculture (CSA).

- CSA is defined by its desired outcomes—agricultural systems that are resilient, productive, and have low emissions.

- Parameters: CSA broadly works on three parameters. These are:

- sustainably increasing agricultural productivity and farmers’ incomes

- adapting to climate change

- reducing greenhouse gas emissions (GHG)

Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA)

- The Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) defines Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA) as an approach that helps guide actions needed to transform and reorient agricultural systems to effectively support development and ensure food security in a changing climate.

- It takes into consideration the diversity of social, economic and environmental contexts, including agro-ecological zones.

- Implementation requires identification of climate-resilient technologies and practices for management of water, energy, land, crops, livestock, etc at the farm level.

- It also considers the links between agricultural production and livelihoods.

- Testing and applying different practices are important to expand the evidence base and determine what is suitable in each context.

|

Can’t organic farming take the lead?

- Organic agriculture is defined by the method of production (no use of synthetic pesticides or fertilisers).

- However, many of the practices used in organic agriculture are climate smart.

- Organic agriculture enhances natural nutrient cycling and builds soil organic matter, which can also support resilience to climate change and sequester carbon in soils.

- But to get more desired results, climate-smart agriculture can be more effective and successful.

What needs to be done?

- The agriculture sectors need to overcome three intertwined challenges:

- sustainably increase agricultural productivity to meet global demand

- adapt to the impacts of climate change

- contribute to reducing the accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere

- Focus on agriculture for inclusive growth: If India is aiming to transition to a green economy and achieve its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), it will have to pay greater attention to the agricultural sector. Agriculture can yet prove to be a catalyst for India to achieve a standard of inclusive, green growth.

- Incentivization towards climate-smart crops: While it is clear that the unsustainable incentivization towards production of rice was due to the procurement system and that the procurement system is largely unequal in its reach, it is nevertheless, a powerful tool to drive the transition towards climate-smart crops.

- Shifting to climate-smart crops: Phasing out procurement of rice and in its stead, creating assured procurement (demand pull) for pulses and millets, at remunerative prices (income support) with subsidised inputs (shadow prices) will ensure a shift to the production of these climate-smart crops, which will aid in India’s green transition.

- Enabling environment: However, in the long run, switching to a more robust alternative for sustainable agriculture will require building an enabling environment with better income support for the farmers.

- Focus on food and nutritional security: The government could then supply the nutritious, climate-smart food-grains to its citizens utilising its PDS and mid-day meal scheme, thereby ensuring food and nutritional security.

The Four Attributes of ‘Transition’

- There are four pillars that will enable a shift to climate-smart agriculture

|

Attributes

|

Mechanisms

|

Impacts

|

|

Sustainable Practises

|

Shadow Prices of Inputs

|

Incentivises production of climate-suitable crops.

|

|

Income Stability

|

Income Support

|

Support against seasonal changes worsened by climate crisis. Balanced flow of revenue to farmers.

|

|

Market Signalling Infrastructure

|

Production as per demand

|

Restrains over-production of certain goods, ensures price and inventory maintained.

|

|

Accessible Enabling Environment

|

Feasible Storage & Processing Facilities

|

Cost of cultivation goes down.

|

|

Better Market Access

|

Easier to sell food-grains.

|

Eco-friendly approaches for farming system

- The Zero Budget Natural Farming (ZBNF): The concept introduced in Andhra Pradesh in 2015 is a low-input, climate-resilient type of farming that encourages farmers to use low-cost locally sourced inputs. It eliminates the use of chemical fertilisers and pesticides.

- Organic farming: It is a production system, which avoids or largely excludes the use of synthetically compounded fertilizers, pesticides, growth regulators, and livestock feed additives. To the maximum extent feasible, organic farming system rely upon crop rotations, crop residues, animal manures, lagumes, green manures, off-farm organic wastes, mechanical cultivation, mineral-bearing rocks, and aspects of biological pest control to maintain soil productivity and tilth, to supply plant nutrients, and to control insects, weeds, and other pests.

- Regenerative Agriculture: In regenerative agriculture bunds on nature’s own inherent capacity to cope with pests, enhance soil fertility, and increase productivity.

- Permaculture: Permaculture is concerned with designing ecological human habitats and food production systems, and follows specific guidelines and principles in the design of these systems.

- Other important approaches include

- zero tillage

- raised bed planting

- direct seeded rice

- crop residue management

- cropping diversification (horticulture, bee keeping, mushroom cultivation, etc)

- Besides, site-specific nutrient management, laser levelling, micro-irrigation, seed/fodder banks can also be adopted.

Recent Government measures to mitigate risks of climate change on agriculture

Foreseeing the future risks of climate change, the Government of India is implementing

- National Mission of Sustainable Agriculture (NMSA), one of the eight missions under the National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC).

- Parallelly, the Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchayee Yojana (PMKSY) envisages “Per Drop More Crop”, that is, promoting micro/drip irrigation to conserve water.

- There is also a push to cluster-based organic farming through the Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana (PKVY).

The mission of these programmes is to extensively leverage adaptation of climate-smart practices and technologies in conjunction with the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) and state government.

Wrapping Up

Given the quantum of the agricultural sector’s contribution to greenhouse gas emissions in India, any movement towards green growth must incorporate the principles of climate-smart agriculture. In turn, taking into account the contribution of rice cultivation to agriculture emissions, any such movement must also incorporate alternatives to improve rice cultivation.

It is therefore important to initiate a new Green Revolution, wherein a just transition towards climate-smart agriculture will incorporate sustainable agriculture planning, provide market signalling and income support, and create an enabling environment through provisioning of processing and storage facilities and better market access.